Of Substance and Relevance; Learning and Experience

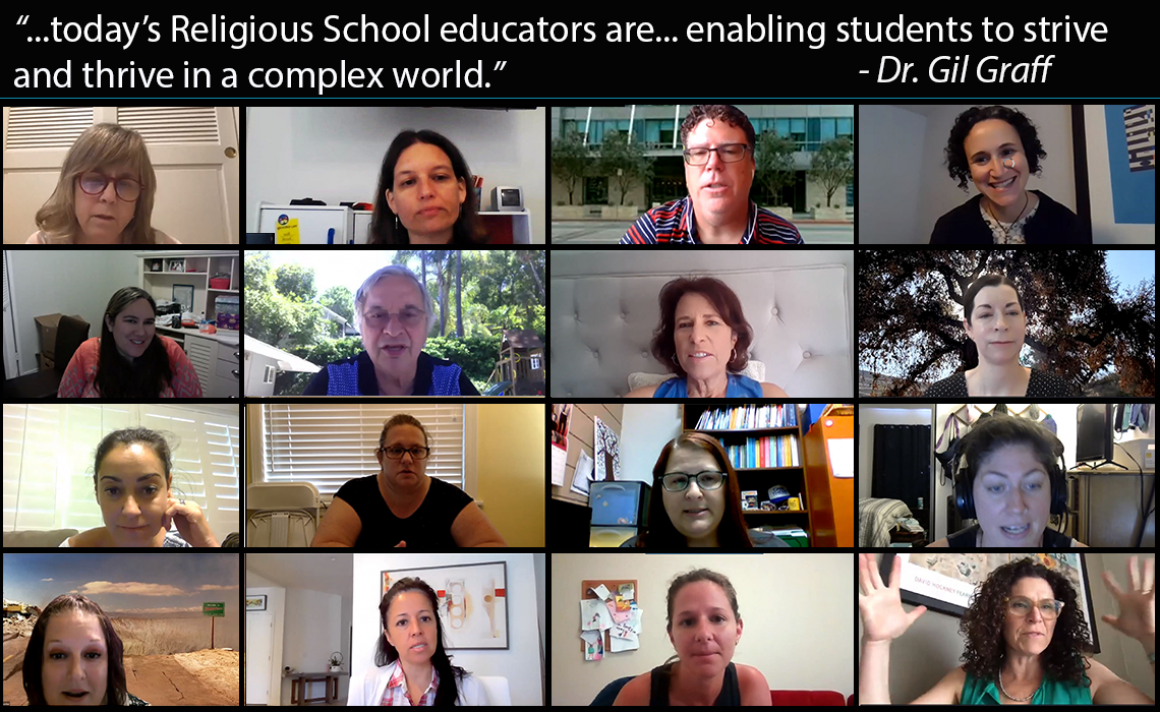

Recently, I attended (via Zoom) a BJE professional development program for directors of education of part-time Religious Schools. As school year 2019-2020 drew to a close, educators were focused on “big picture” thinking, looking ahead to next year. In a keynote address, Dr. Miriam Heller Stern, Director of the Schools of Education of Hebrew Union College, spoke of nurturing creative Jewish sensibilities through education.

Listening, in this context, to Dr. Heller Stern – an educational thought leader who, to the very good fortune of L.A. students and colleagues, is locally based –

I couldn’t help but reflect on my earliest experience teaching students at a part-time Religious School. As a college student in Chicago, I complemented my daytime studies, as a freshman at the University of Illinois, with courses in the afternoon and evening at the College of Jewish Studies (later, Spertus College of Judaica and, today, Spertus Institute). The (non-denominational) College of Jewish Studies offered a rich array of Jewish learning opportunities as well as a teacher education program in which I was pleased to participate.

As a rising sophomore, soon to turn 18 years old, I presented myself as a candidate for a teaching position at the Religious School of a Reform Temple in a nearby suburb.

![]()

The principal, a public school educator by profession, was pleased that I was studying education and continuing my own Jewish studies; he imagined that I might connect well with the school’s students. I was hired, and received two books which were to serve as the bases for class sessions with the students in fifth grade whom I would soon meet.

One book, The Rabbis’ Bible, was an abridged version of the Torah, with commentary drawn from rabbinic lore printed beneath selections from the Torah. The rabbinic teachings that were included aimed to make the Torah passages relevant to the lives of the students. The second book, At Camp Kee Tov, drew the reader into a summer camp setting with each chapter presenting a dilemma of the sort that emerges in the course of interactions at camp. Jewish wisdom, often drawn from Pirkei Avot, expressed through a camp personality known as “Gramps,” would typically open the door to reflection upon and resolution of the challenging situation. I was impressed with these books, grounded in Jewish sources and speaking to the lives of the children who read them; students seemed to appreciate both the substance and relevance of the texts and the ideas which we explored together.

At the very time I started teaching, Professor Joseph Schwab was (at nearby University of Chicago) writing about what he termed “commonplaces” of education. He pointed to the need for curricula to take due notice of learners, teachers, subject matter and the milieu. Not unlike John Dewey, in an earlier generation, Schwab understood the importance of students’ interaction with the curriculum and students’ taking an active part in their own learning. With a focus on the learner, today’s Religious School educators are, in keeping with the vision articulated by Miriam Heller Stern, enabling students to strive and thrive in a complex world. The Jewish wisdom to which they introduce their students is an enduring treasure, speaking to successive generations, throughout time and place.

Dr. Gil Graff is the Executive Director of BJE.